“Vivienne Westwood, The Sex Pistols, Seven Stars, coffee with milk and strawberry cake. And Ren flowers. Nana’s favorite things never change.”

Ai Yazawa’s beloved manga series Nana is turning 25, and Vivienne Westwood is stepping in to celebrate.

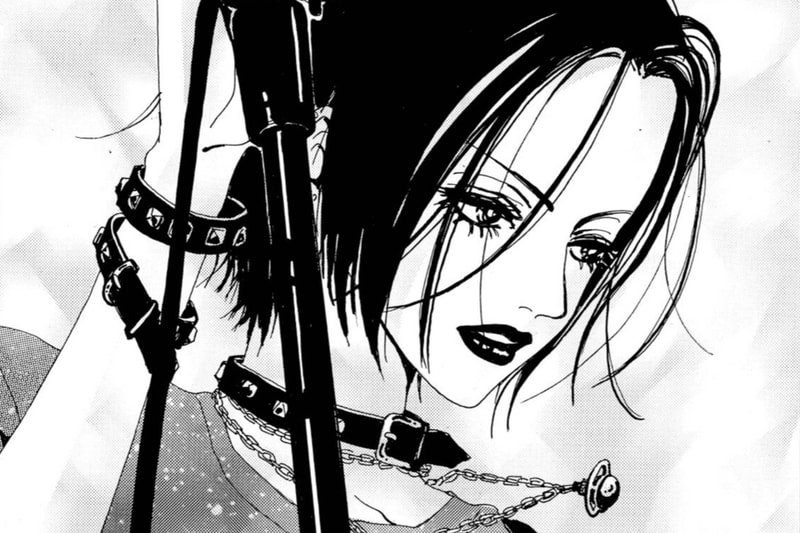

Last month saw a special, anniversary re-edition of Volume 1, complete with a new cover of heroines Nana Osaki and Nana Komatsu dressed in head-to-toe Westwood and, of course, a tartan-printed spine, though the full Vivienne Westwood x Nana collection, now available online, takes the collaboration off the page. Featuring a range of garments, accessories, jewelry and footwear, the collection plays off the personal style of both leads, spanning Komatsu’s coquettish flair to Osaki’s hard-edged punk.

Alongside new items are contemporary evolutions of archival styles featured in-print, like Rocking Horse platforms, the Stormy Jacket from the Autumn-Winter 1996/97 ‘A Storm In A Teacup’ collection, the return of the iconic Armour Ring and a trove of brand logo exclusives. Among the most highly-coveted items is the Nana Giant Orb Lighter, which took on new life throughout the years, with fans dubbing replicas as Nana merch.

The collection closes a loop on a long-standing love affair between punk dames, Osaki and Westwood. From the start, the brand has played an essential role in shaping the series’s visual universe, with the collaboration already making history as one of the most exciting fashion-fiction cross-overs – think Jean Paul Gaultier’s sci-fi fits in Luca Besson’s The Fifth Element (1997) or Manolo Blahnik’s hand in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006). In honor of the official Vivienne Westwood x Nana release, we’re taking a look back on the shared history of two subcultural titans who reshaped the look of rebellion.

Punk emerged in the U.S. and U.K. during the mid-1970s as a middle finger to authority, establishment and the hollow promises of consumer culture, and Westwood cemented a legacy as one of its original provocateurs. Before establishing her namesake label, Westwood, a school teacher by day, designed clothes for the Sex Pistols with her then-partner and band manager Malcolm McLaren, forging a stylistic identity that accelerated both the band’s career and the punk subculture at large. In London, all eyes were fixed on the couple for their “anti-fashion as fashion” flair, leading them to open SEX, a tiny King’s Road boutique remembered for its collection of leather goods, fetish wares and bondage garments.

After splitting with McLaren, Westwood’s designs took on a “New Romantic” feel — most recognizable in Nana — building off the couple’s first runway collection, ‘Pirate.’ Ripped shirts and safety pin-clad pieces gave way to lace, pearls and flouncy skirts. Serving up her own spin on high culture — structured silhouettes, heritage fabrics and jewel-heavy accessories — the designer kept on her path of sartorial rebellion, but this time, by challenging the establishment from within.

To open her first international store Westwood took to Japan, and by the time she arrived in Tokyo, her designs already had a tight grip on the city’s fashion scene. Finding new aesthetic legs, the distinctly Japanese interpretation of British punk kept the movement’s countercultural ethos at heart, while adopting a greater focus on unapologetic self-construction, and Yazawa’s magnum opus, captured that duality perfectly.

For those unfamiliar, Nana follows the story of two unlikely friends, up-and-coming punk songstress Osaki and Komatsu, a hopeless romantic, as they navigate their own ambitions and paths of becoming. “For me, drawing a punk band and drawing Vivienne’s clothes could not be separated,” Yazawa explained in a recent interview with the Westwood brand.

Born in 1967 in Amagasaki, Hyogo, Yazawa grew up in an era of seismic shifts for art and fashion, thanks to international names like Westwood and Japan’s own “Big Three,” Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto. Captivated by this world, she enrolled in fashion design school, though left to pursue her career as a manga illustrator full-time in Tokyo.

With this, it comes to no surprise that Nana is lauded as one of the most fashionable series, with pages full of fashion deep-cuts. “Almost all of the pieces came from my personal collection,” Yazawa said. “Vivienne has always been, and still is, the creator I respect most.”

In Nana, clothing double as doors into the emotional interiors of its characters: Komatsu’s frilly pinks and whites reflect a warm, albeit naive, sense of optimism, while Osaki embodies punk in the classic sense, a means to declare autonomy against the tight confines of social, namely gender, norms. She makes clear that punk is a philosophy of living on your own terms, even if when those terms hurt — a tension best encapsulated by her Armour Ring, now one of the brand’s bestsellers, as a reminder of that even our strongest need protecting sometimes.

Taking direct influence from the Westwood story — from Osaki’s tough road to self-made punk stardom, to her volatile romance mirroring that of Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen — beyond its visual vocabulary, it’s the vulnerability and history that makes the fashion of Nana/em> feel earned.

Even two decades on, its Nana‘s spirit of creative defiance and self-expression that inspires new generations of fans, and much like the late, tartan-loving designer herself, its enduring appeal rests in its relentless pursuit of potential, against the noise. While there’s yet to be an official series ending in sight, the collaboration rekindles this fashion-art dialogue at the heart of Yazawa’s work, culminating in, as she describes, a “punk love letter that honors the past, present and future of Nana.”

Click here to view full gallery at Hypebeast

Clark County health officials warn families about national infant formula recall linked to botulism cases

ByHeart has voluntarily expanded its recall to include all batches of its Whole Nutrition Infant Formula, including both cans and single-serve Anywhere Pack packets.| Play | Cover | Release Label |

Track Title Track Authors |

|---|